Wednesday, January 23, 2019

Tragedy Near McLellan

Tuesday, January 15, 2019

The Turpentine Feud of 1911

Wednesday, June 27, 2018

Friday, August 11, 2017

The Acreman Family Murder

On that morning, a neighbor,

living about a quarter a mile away, looked toward the Acreman place, but did

not see the house. He contacted other neighbors, and a group of them

found the Acreman house in smoldering ruins. Upon closer investigation,

they found the burned bodies of the family. One member of the group went

to a nearby turpentine camp, and called the Sheriff's office in Milton.

Judge Rhoda, Sheriff David Mitchell,

Dr. H.E. Eldridge, and several others, hurried to the Acreman home.

Upon arrival, the ruins were still

smoking. A stiff northwest wind was blowing, and cinders were found a half of a

mile away from the scene. It is believed that the house the Acreman’s were

murdered in was located on present day State Highway 87, where it is joined by

Sonny Dozier Rd. Nothing remains today, but that site is approximately 10 miles

north of downtown Milton, and that was the description in contemporary news

accounts.

W. G. Acreman was the son of

Zebulon Rudolph Acreman, and was most likely born in 1869 in Lowndes County,

Alabama. He had eight brothers, and one sister. He was described as being a

peaceful, pious, and harmless man with no enemies.

In 1902, the Acreman's were

living in Mobile, Alabama near the corner of Selma, and Marine Streets.

Described as being in desperate circumstance, they were helped by their church.

Mr. Acreman was remembered there as a peaceful, harmless man who was very

religious, and a bit eccentric. He had no known enemies.

Apparently,

they left Mobile, and settled in Opp, Alabama for about a year, and sometime in

1903, moved to the area where they eventually died. Acreman had been married at

least three times. One marriage record has been found. He married Timathea

Nippee, or Nipper, in Escambia Co., Alabama on 5 Feb 1893. He was also married

to Mary Simmons of Brewton, Alabama. His last wife was Amanda Sorrells who died

that night with her newborn baby. Amanda was most likely the daughter of David

W. Sorrells who lived in Pine Level, a community near Jay, Florida, a few miles

from the Acreman home. Acreman had a daughter that survived. She was from his

marriage with Mary Simmons, and was staying with an Aunt in Selma, Alabama.

The Crime Scene

Acreman was working as a

sharecropper, and the family was desperately poor. The house they resided in

was described as a two-room “L” shaped house with two doors in front, one each

opening into each room. Directly opposite were two doors going to the back porch.

The house had numerous windows, and the front of the house faced north.

Acreman, and one son shared a bed in the southeast corner of the east room. His

wife, and 3-day-old infant slept in a bed in the same room, directly opposite.

Three boys slept together in the southeast corner of the west room, and

directly opposite of them was the bed of two daughters, the oldest being around

14.

In the ruins of the house, Acreman

was found near the sill of the door leading from his room to the back porch. A

gun was found by his side. His skull was crushed, and upon examination a large

blood clot was found at the base of his skull leading authorities to believe he

was killed before the fire. His body, as all the others, was burned very badly.

His wife and infant baby were found on the front porch, and it was believed

they were killed outside. The condition of her skull indicated she was killed

before the fire. The boys, and the younger of the two girls were apparently

either killed in bed since their remains were found where their beds were

located. The oldest girl was found just inside the door leading to the front

porch.

There was a subscription in

Milton, and Bagdad to raise money for a reward for information. An amount of

$1500 was quickly raised, but there were no immediate developments in the case.

The list of contributors reads like a Who’s Who of Milton in 1906:

H.S. Laird - $50, Prosecuting Attorney

David Mitchell - $100, County Sheriff

Balentine & Whitley - $50, Manufacturer, Naval Stores

Franklin S. Gay - $25, Turpentine Camp Operator

John T. Salter - $10, Railroad Carpenter

Charles E. Elliott - $100, farmer

E. M. Gainer - $50, possibly Ella Gainer, wife of Jim,

W. F. Harrison - $25

C. D. Bass - $5, Day Laborer, in 1900.

D. P. Johnson & Son - $25

Robert C. Fleming - $5, mill worker

R. E. Peterson - $5, fisherman

Howard Jernigan - $10, 1900 he was a census enumerator

Fisher & Hamilton - $50

Fisher & Co. - $50

G. L. Abbott - $5

Thomas W. Jones - $10, mercantile store

J. A. Allison - $5, keeper of Poor House

J. B. Ellis - $10, farmer

Howard S. Bates - $5, dry goods, (1910)

Cohen Bros. - $50, General Merchant

Milton Drug Co. - $25

Dr. C. B. McKinnon - $25

Frank E. Dey - $10, jewelry shop

M. N. Fisher, Sr. - $5, night watchman

I. M. Josephson - $5, dry good merchant

A. Moneyway - $5

D. T. Williams & Co. - $25

Lawrence Brown - $5

Dr. W. A. Mills - $10

The Milton Index - $10, Local Newspaper

H. C. Monroe - $5

W. W. Allen - $25

Lewis P. Golson - $50, Clerk

P. T. Macarthy - $10

D. B. Whitmire - $25, tax collector

Willis W. Harrison - $10, hatter

J. C. Gay - $10

Walter Rivenbark - $10, turpentine laborer

Allen & Allen - $25

E. P. Holley - $25, County Judge

E. L. Daniel - $25

R. M. Jernigan - $5

Lewis M. Rhoda - $5, Judge

Chaffin & Co. - $50

J. C. Day - $10

W. A. Waller - $10

R. C. Helms - $25

Morris Littles - $25

D. F. Johnson - $50

J. A. Bryant - $50

Charley H. Simpson - $25, farmer

Dr. H. E. Eldridge - $25

C. P. Jernigan - $10, butcher

J. E. Spencer - $10

Alexander H. Allen - $20, farmer

From Bagdad:

Stearns-Culver Lumber Co. - $100

B. Greenwood - $10

Asbery P. Hardy - $25, retail merchant

Bagdad Manufacturing Co. - $75

Steward Bros. - $25

Dr. B. H. Alles - $10

A.

Nicholson - $5

Capt. John Rourke - $5, sawmill owner,

Confederate vet.

Aycock & Co. - $10

R. E. Barnes - $5

In 1906, crime investigation was extremely primitive. There were no

trained investigators in Milton, no idea about forensics, or crime scene

preservation, so a reward fund would be raised, and private investigators would

arrive with hopes to solve the case, and collect the reward. Eventually the

reward fund reached around $2300 including $500 from the State. This was how

big, headline making crimes were investigated in those days. Private Investigators,

some real, some no more than con men seeking to bilk communities out of their

reward money, would seek out these opportunities. The Acreman crime brought a

man named Ralph Clifford Beagle, claiming to be an investigator. All that I can

find out about him is that he was born, and raised in Saginaw, Michigan, and in

the 1900 census he is staying in a hotel on Ship Street in St. Joseph, in

Berrien County, on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan with his occupation

listed as a travelling salesman.

Beagle claimed

he was a detective, and apparently did work hard to solve the case. About a

year after the murder, Beagle physically took part in getting warrants, and

making two arrests with help from local police.

In Gonzales, Florida, William C. Smith, (I believe this

was actually a man named Kitchen Willie Smith., or William K. Smith. I found

him buried in Monroeville, Alabama with his wife, Eliza Jessalena Smith who

died on 14 April 1907.) was arrested and brought to Milton. He was living

in Allentown at the time of the murders, and when his wife died in 1907, he

took her remains, and his six children to Monroeville, Alabama. Some articles

suggested that he confessed, but if so, his confession must not have been

believable.

In Samson, Alabama, located in Geneva

County, and not far from Opp, detectives arrested Joe Stanley. Stanley

must have had a fearsome reputation, because the detectives employed some

subterfuge to get the drop on him. They visited his farm asking if he had

any tacks, they could use to put up a sign with. When Stanley turned to get

some one of the detectives got the drop on him, and he was arrested at

gunpoint. After the warrant was read to him, Stanley asked if he could

get some clothes from a trunk. The detectives refused, but opened the trunk

themselves, and found no clothes, but did find two pistols there. Stanley

also attempted to get his hands on a shotgun, with no success. Stanley

had a wife and two children, and refused to waive extradition to Florida. After

the right paperwork was obtained, he was removed to Santa Rosa County, Florida.

There was a hearing scheduled

for May 15, 1907 in Judge Rhoda’s courtroom, and it was postponed when state

witnesses could not be located, and a stenographer was not available. I

found another article that claimed the prosecutor, and judge were under death

threats, and did not show up for court. Regardless, two days later there

was a brief hearing, and both suspects were released. The case is officially unsolved.

When Stanley was arrested, the

Troy (Ala) Messenger published an article that mostly reported the same

information as the other papers, but they added that, “Stanley has been under

suspicion as he is said to have had trouble with the murdered man.”

No other references to this “trouble” could be found. When the

Acreman’s moved from Mobile to Opp, did Mr. Acreman have some kind of run-in

with Stanley? I got a message over a year ago, stating that the farm

Acreman was working was owned by the Stanley family of the Opp area.

There are many articles, in southern

Alabama newspapers about confrontations with the law by Joe Stanley. It’s not

possible to know if there were multiple Joe Stanley’s living in the area during

the same time frame. There was an article added to Joe Stanley’s Find A

Grave memorial that told the story of Jocephus Stanley’s death on March 8,

1928. I pretty sure this is the same Joe Stanley that had been arrested

in the Acreman murders. Stanley was a policeman in Phenix City, Alabama,

which is just across the Chattahoochee river from Columbus, Georgia. In

the middle of the river on an island that is sometimes claimed by both Alabama,

and Georgia, Stanley was shot during a confrontation with a gang of gamblers,

and bootleggers that based themselves in the “no man’s land”. Stanley was

attempting to arrest a George Chambers who was a customer of James

Jennette. Stanley had been informed of some threats directed at him and

went to ask Jennette about it. During the confrontation, Jennette pulled

a pistol and fired three shots. Two missed, but the third hit Stanley in the

stomach. Another officer hit Jennette in the head, and at the same time Stanley

backed off a few feet, and fired one time, hitting Jennette in the body.

They were loaded in the same car and taken to the hospital, where both died.

His body was brought back to Opp where he was buried.

William K. Smith, or Kitchen Willie

Smith died in 1916, and is buried with his wife in Monroeville, Alabama.

Ralph Clifford, (R.C.) Beagle died in Pensacola of Tuberculosis on 12 July 1907, and his body was escorted by his sister back to Michigan and buried at the Brady Hill Cemetery in Saginaw.

The Acreman family is interred in one mass grave in the Jay

Cemetery. The grave is next to Amanda’s parents, and an older brother. Their headstone has the quote:

“No pain, no grief, not anxious fear can reach our loved

ones sleeping here.”

Afterword

There is a very well written book by

Bill James, and his daughter, Rachel, titled: The Man from The Train, The Solving of a Century-Old Serial Killer

Mystery.

It is the story of a long series of

Axe murders across the country that occurred from 1898 through

1912. The Acreman murders near Allentown, fit right into this

narrative. Even setting the fire after the killing was part of the

killer’s technique. He quite possible killed over 100 people in this

manner and rarely left any survivor.

The Villisca Iowa killing of

the Moore family is also part of this story. He makes a rather

compelling case, due to the similarities among these many, many

murders. The fires, proximity to rail road tracks, covering the face

of some of the victims, and many more examples.

The suspect was a German

immigrant named Paul Mueller who killed his first victim in Brookfield,

Mass. Many of his murders occurred in rural areas close to logging

which is probably how he supported himself. He never robbed his victims,

usually leaving valuables in plain sight.

It is a very compelling case study. Were the Acreman’s killed in a random manner

by a psychopath riding the rails? It is hard for me to believe that Stanley,

and Smith could have done something like this. I don’t think it would have been

the only case of this type in the area, if that was the case. Likely, we will

never know for sure.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Sunday, July 23, 2017

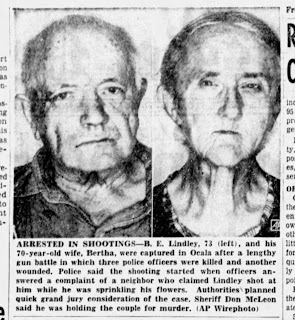

Retired School Teacher Kills Three Police Officers

Saturday, July 1, 2017

Unsolved Pensacola Axe Murder, 1926

What is now a segment of W. Hilary St. in Pensacola, once was known as Chipley Alley. It lies just south of W. Garden St. between S. Coyle St. and S. Reus St. It was near the site of the old Frisco railroad freight and passenger terminal building. On the night of July 4, and early morning of July 5, 1926, 410 Chipley Alley was the site of a vicious attack on two adults, and two children by an axe-wielding madman.

Preston Pickren's body was transported to the Godwin Cemetery in Bratt, located in the northern part of the county. (See picture below.)

Thursday, June 22, 2017

The Unsolved Murder of Henry Hicks Moore

There was another killing in a secluded parking area, before the Hinote, Bryars, killings. The location of this one was in the Magnolia Bluffs area off of Scenic Highway. This occurred months before the last one I wrote about, and is also unsolved.